Workload Architecture Design Specification

If Someone New Can’t Build and Operate From the Doc Without a Meeting, Your Architecture Isn’t Finished

Architecture isn’t the diagram.

Architecture is the set of decisions that let a team build, run, secure, recover, and evolve a workload on purpose.

That’s why Microsoft’s guidance around workload design consistently points back to being explicit: document design choices, justify them, acknowledge tradeoffs, and make sure the design supports routine, ad hoc, and emergency operations.

A Workload Architecture Design Specification is how you do that.

North Star: If someone new can’t implement and operate your workload using the spec - without a meeting - your architecture isn’t finished.

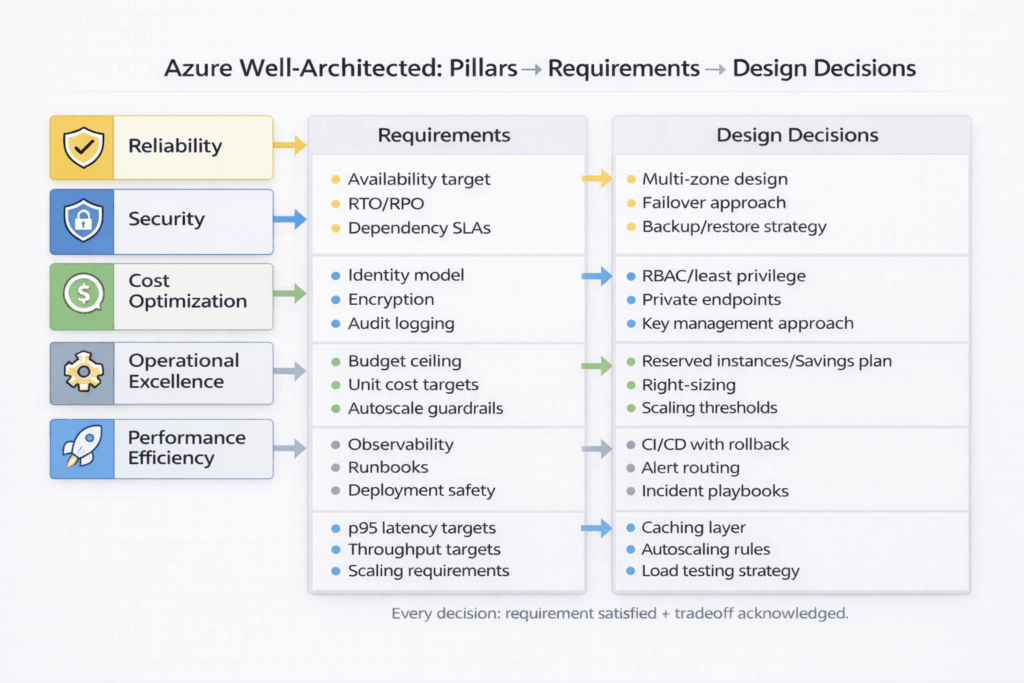

Where the Azure Well-Architected Framework fits

The Azure Well-Architected Framework (WAF) is the foundation for making high-quality workload decisions. It helps you evaluate and design across five core pillars:

- Reliability (uptime, resiliency, recovery)

- Security (confidentiality, integrity, identity, governance)

- Cost Optimization (value, spend control, waste reduction)

- Operational Excellence (observability, automation, safe change)

- Performance Efficiency (right resources, scaling, responsiveness)

Your architecture design specification is the artifact that turns WAF intent into implementation reality.

In practical terms: Every major decision in your spec should answer two questions:

1. What requirement does this satisfy? (functional or nonfunctional)

2. Which WAF pillar does this strengthen, and what tradeoff does it introduce?

Start where Microsoft starts: business clarity

Before you pick services, patterns, or regions, you need alignment on business goals and constraints. If you don’t have that clarity, you’ll end up with “solution-first architecture” that looks good on paper and fails in production.

Your spec should open with:

- Business outcomes (what success means)

- Constraints (budget, timeline, compliance, data residency, tooling)

- Users and scenarios (who uses it, how they use it)

- Risk posture (what can fail vs. what must not)

This is how you keep the design rooted in purpose—especially when tradeoffs appear.

What a Workload Architecture Design Specification actually is

A workload architecture design specification is a detailed, unambiguous design blueprint that describes:

- The overall architecture and key components

- The design choices (and why)

- How it meets functional and nonfunctional requirements

- How the workload will be built, deployed, monitored, operated, and recovered

It’s typically created collaboratively (architects, devs, ops, security, product owners, testers), refined through reviews, and treated as a plan-of-record during implementation.

[Image Placeholder #2: High-level workload architecture diagram with labeled components and data flows]

Functional vs. nonfunctional requirements (and why this matters)

Most teams are decent at documenting what the app should do.

Where architectures fail is the nonfunctional side:

- Availability and recovery targets

- Security constraints

- Operational needs (monitoring, incident response, patching)

- Performance expectations

- Cost boundaries

WAF is your guardrail here. Nonfunctional requirements map naturally to the pillars.

A simple way to structure requirements

Include a “Requirements Matrix” that translates business goals into measurable requirements.

Example structure:

- Reliability: availability target, RTO, RPO, error budget, dependency SLAs

- Security: identity model, data classification, encryption, auditing, threat model

- Cost: budget ceiling, unit cost target, scaling cost boundaries

- Operational Excellence: deployment frequency, MTTR goals, on-call expectations, runbook coverage

- Performance Efficiency: p95 latency targets, throughput targets, scaling requirements

[Image Placeholder #3: Requirements Matrix table mapped to WAF pillars]

The core sections your spec should include

Below is a structure that aligns strongly with WAF guidance and keeps your implementation teams out of ambiguity.

1) Scope, context, and assumptions

- Workload overview (purpose, value)

- In-scope vs out-of-scope

- Assumptions and dependencies

- Stakeholders and responsible teams

2) Architecture overview (the “what”)

- Component diagram(s)

- Data flow diagram(s)

- Trust boundaries and network zones

- Key integrations

This is where diagrams belong—but diagrams aren’t enough without decisions.

3) Design decisions and tradeoffs (the “why”)

This section is the difference between “documentation” and “architecture.”

For each major decision, document:

- The decision

- The requirement(s) it satisfies

- The WAF pillar(s) it supports

- The tradeoffs accepted

- Risks introduced and mitigations

Pro tip: Use an Architecture Decision Record (ADR) style so decisions are consistent and auditable.

[Image Placeholder #4: Example ADR card showing Decision → Alternatives → Tradeoffs → Impacts]

4) Technical specification (the “how”)

This is the engineering plan-of-record. Include items like:

- Technology decisions: buy, build, reuse, extend, decommission

- API and data contracts: schemas, versioning, backwards compatibility strategy

- Rollout and rollback: deployment steps, progressive exposure, feature flags, rollback triggers

- Secure development lifecycle (SDL) + privacy: required practices, scanning, secrets handling, data minimization

- Test plan: unit/integration/e2e, performance testing, chaos/fault injection where appropriate

- Key monitoring and alert signals: what you monitor, what triggers action, who owns signals

- Alternatives considered: what you didn’t choose and why

This section should be explicit enough that work items can be created directly from it.

5) Operational design (routine, ad hoc, emergency)

WAF is clear that architecture must support real operations, not just “happy path” usage.

Include:

- Routine operations: scaling, patching, certificate rotation, access reviews

- Ad hoc operations: reprocessing, tenant onboarding/offboarding, manual remediation

- Emergency operations: incident triage, failover, break-glass access, containment steps

Tie every operational requirement back to Operational Excellence and Reliability.

[Image Placeholder #5: Ops workflow diagram: Change → Observe → Respond → Improve]

Disaster Recovery: make RTO/RPO real

If your workload has reliability requirements, your architecture design specification must include the initial DR plan.

At minimum, cover:

- Target RTO (how quickly you must recover)

- Target RPO (how much data loss is acceptable)

- Recovery scope (what must recover vs what can be deferred)

- The recovery approach (backup/restore, active/passive, active/active)

- Failover mechanisms and triggers

- User and data flow impact during recovery

- Operational recommendations and runbooks

Also be explicit about what recovery targets are met by design—and what requires additional investment.

The plan will evolve as you run drills and learn from incidents, but the architect owns delivering the initial plan.

[Image Placeholder #6: Multi-region deployment + failover diagram with traffic routing + data replication]

Security and compliance: document the affordances and the gaps

Architects are responsible for designing solutions that adhere to security and compliance constraints.

Your spec should highlight:

- Identity and access model (roles, least privilege, privileged access)

- Network segmentation and trust boundaries

- Data protection (classification, encryption at rest/in transit, key management)

- Logging and auditing (what’s logged, retention, access to logs)

- Threat modeling inputs and mitigations

- Compliance requirements and how the design supports them

When a requirement can’t be met directly, call out compensating controls.

[Image Placeholder #7: Security architecture diagram with trust boundaries + controls mapped]

Consistency: the template is a force multiplier

Most architecture pain comes from inconsistency:

- One team documents decisions; another doesn’t

- Specs live in random places

- Stakeholders can’t find who approved what

Use a standardized template and include essential metadata:

- State: Draft / In review / Approved

- Work item link: primary backlog epic or feature link

- Key cross-links: threat model, runbooks, test plans, diagrams, ADRs

- Key individuals: decision makers and approvers (roles + names)

Store specs with the workload documentation, keep them discoverable, and treat them as living artifacts that get updated as the workload evolves.

A practical “Definition of Done” checklist

Before you call architecture “finished,” use this quality gate:

- Does the spec clearly state business outcomes and constraints?

- Are functional and nonfunctional requirements explicit and measurable?

- Are decisions tied to WAF pillars and tradeoffs documented?

- Are alternatives considered captured for major decisions?

- Are rollout and rollback paths real, tested, and trigger-based?

- Is monitoring defined with actionable signals and ownership?

- Can an operator follow runbooks for routine and emergency operations?

- Are RTO/RPO targets documented with a concrete recovery strategy?

- Are security/compliance constraints met—or compensating controls defined?

- Could a new engineer implement and operate this workload without a meeting?

If you can’t confidently check these boxes, you don’t have a finished architecture—you have a draft.

Copy/paste starter template (lightweight)

Use this as a minimum viable spec outline:

Workload Architecture Design Specification

Metadata

- State: Draft / In review / Approved

- Owner:

- Approvers:

- Work item link:

- Last updated:

- Related docs:

1. Business Context

- Outcomes:

- Constraints:

- Users + scenarios:

2. Requirements (Mapped to WAF Pillars)

- Reliability:

- Securit